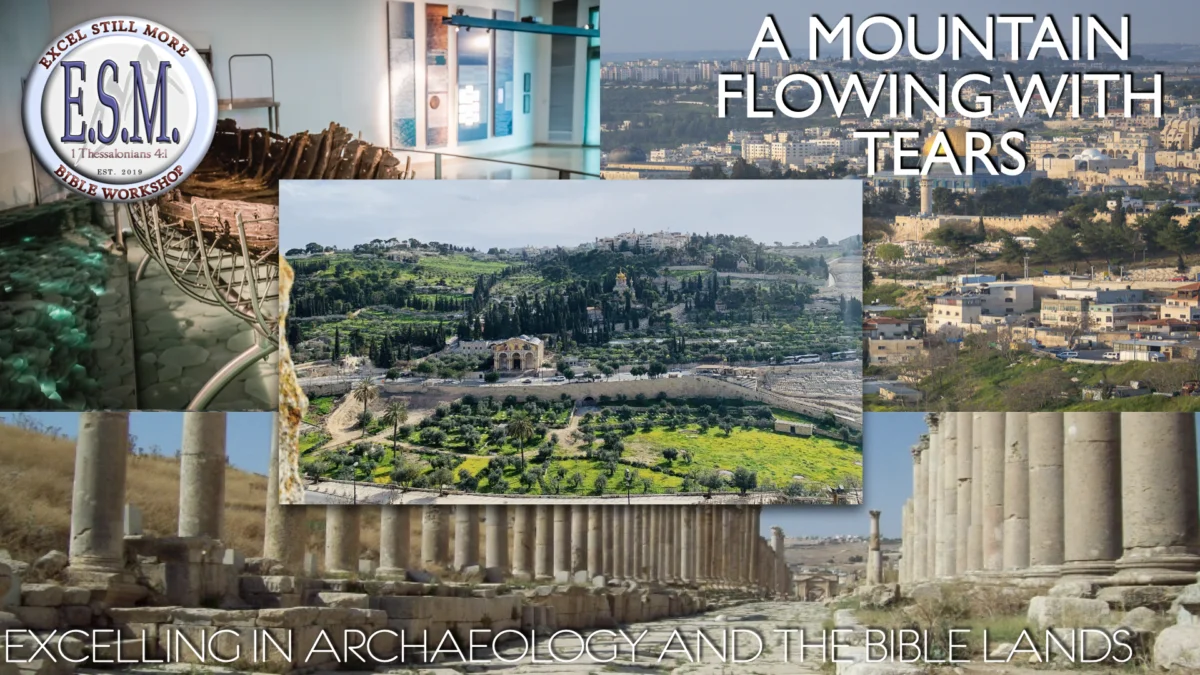

With his head covered, barefoot, and weeping, David hurriedly left the city he had helped to conquer and build. His Kingdom was in turmoil. Government officials had betrayed him. Friends had become traitors, and David’s estranged son, Absalom, had led a coup to overthrow his own father. As his rebellious son led an entourage of soldiers toward Jerusalem, David and the rest of his family found themselves fleeing an imminent government takeover (2 Sam. 15:1; 16:15-19). Leaving the comfort and protection of his Jerusalem palace, David and his family walked down the hill across the brook of Kidron and tearfully ascended the famed Mountain of Olives on their way to the desert of Judea (2 Sam. 15-16). It would not be the last time that the hallowed ground of this historic mountain would feel the weight of sorrow. The Mountain of  Olives have often flowed with tears—in Bible times and still today as Christian pilgrims from all over the world stand atop its highest point to look out over the historic sites where Jesus lived and died and where numerous other Bible events unfolded.

Olives have often flowed with tears—in Bible times and still today as Christian pilgrims from all over the world stand atop its highest point to look out over the historic sites where Jesus lived and died and where numerous other Bible events unfolded.

First mentioned in 2 Samuel 15:3, the Mountain of Olives is mentioned both in Old and New Testament texts alike (e.g., Zechariah 14:4; Nehemiah 8:15; Ezekiel 11:23; Acts 9:1-12). Over the years, it has contained various olive vineyards along its peak and on its terraced slopes. Standing at some 2652 feet above sea level, it is part of a continuous ridge of hills that runs parallel to the modern and ancient cities of Jerusalem. It is approximately 150 feet higher than Mount Zion, upon which the Herodian temple complex once stood.

The ridge on which the Mountain of Olives is located is just east of the ancient city of David and across fromthe temple mount, with the Kidron Valley lying between. This valley progresses from north to south, cutting its way along the base of the Temple Mount. Further south, it runs along the hill and spur of Ophel, where the earliest inhabitants of Jerusalem built their city near the spring of Gihon. Later, after conquering the city from the Jebusites, David built a palace and fortress in the nearby vicinity (2 Samuel 5:6-10).

Sadly, just across the valley from David’s residence, Solomon built a temple and established a high place to appease his foreign wives (1 Kings 11:6-7). The site became known as the Hill of Offense (more accurately translated as “destruction”) and would have been easily in view of God’s holy temple, having been built on an even higher hill than the Temple Mount. As pilgrims emerged from the Judean Hill country, longing to see God’s holy temple, they would have easily seen the pagan shrines built to Molech and Chemosh just across from God’s noble sanctuary. Truly, tears of anger and sorrow must have flowed from the eyes of God’s faithful to see such an abomination so easily accessible and visible to visitors of the sacred city. If David could have looked down the stream of time to see how his son so blatantly violated God’s covenant by erecting a pagan shrine, especially so near to God’s noble sanctuary, he would have undoubtedly wept a thousand tears.

Sadly, just across the valley from David’s residence, Solomon built a temple and established a high place to appease his foreign wives (1 Kings 11:6-7). The site became known as the Hill of Offense (more accurately translated as “destruction”) and would have been easily in view of God’s holy temple, having been built on an even higher hill than the Temple Mount. As pilgrims emerged from the Judean Hill country, longing to see God’s holy temple, they would have easily seen the pagan shrines built to Molech and Chemosh just across from God’s noble sanctuary. Truly, tears of anger and sorrow must have flowed from the eyes of God’s faithful to see such an abomination so easily accessible and visible to visitors of the sacred city. If David could have looked down the stream of time to see how his son so blatantly violated God’s covenant by erecting a pagan shrine, especially so near to God’s noble sanctuary, he would have undoubtedly wept a thousand tears.

One thousand years after Solomon, Jesus would also tread upon this infamous mountain. Jesus was like David, and His tears were shed because of the sorrow connected to sin, but instead of running away from trouble and into the wilderness, the Son of God descended in painful tears toward a city that would torture and murder him. Luke’s gospel tells us that as Jesus made his way down “the ascent of the Mountain of Olives” and on his way to Jerusalem, “He wept over it” (Luke 19:41). “Wept” from the Greek word klaio was often “used to express violent emotion” and indicates to us the intensity of his feelings on this occasion.

His cries, however, were not for Himself but for the people of Israel, whom He loved so much. “Oh Jerusalem, Jerusalem…how often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, but you were not willing” (Matt. 23:37. ESV). Just days later, He would once again open the floodgates of emotion as He wept alone in the garden of Gethsemane (Matt. 26:36-46).

Today on the Mountain of Olives, numerous “holy” sites commemorating various biblical events adorn the landscape of this well-known hill. At the top stands the Church of the Ascension, where it is believed that Jesus gave His final commission before departing to be at the Father’s right hand (Acts 1:12f). Near the middle, a Russian church building exists dedicated to Mary Magdalene. But near the base of this mournful mountain lies a grove of olive trees and the Church of all Nations (The Basilica of Agony), where it is alleged by some that Jesus spent the night in prayer prior to his crucifixion. Others suggest that the Lord’s painful tears occurred in a cave at the base of the mountain, where archaeologists discovered an ancient olive press dating to the time of Christ. This is a striking connection when we remember that Gethsemane means “place of the press” and that Jesus was being pressed and burdened by the events which awaited Him in the vicious scouring and vile crucifixion.

Whether in an olive grove or in a cave with an olive press,

Jesus’ mournful and solemn prayers of anguish were uttered not only for the events to follow but for you and me. You and I and the rest of sinful humanity are the ones for whom He was crying. It was for me that He was being made “very sorrowful, even to death” (Matt. 26:38, ESV) and spent the night praying that His cup of agony might somehow be removed (Luke 22:41-44). However, because of sin’s tragic consequences, the perfect and beautiful rose of Sharon had to be crucified, and it was on this historic ground that sweat drops of blood poured from His brow, and with “loud cries and tears,” He offered up prayers and supplication (Heb. 5:7). As the songwriter Samuel Reed said, “Long in anguish deep was He, weeping there for you and me.”

Yes, the Mount of Olives was a place for tears. Even today, a small church building designed in the shape of a teardrop has been erected on its slope.

It is called “Dominus.”

Flevit”, which means “the Lord wept.” Its purpose is to remind those who visit this cherished site of the sorrow He bore two thousand years ago on that hallowed hill near Jerusalem. Each time I see the site, whether in person, on video, or in a photograph, I am reminded of both the tragedy of sin and the love of our Savior. I am also reminded that Jesus wept, cared, and suffered so much to reveal to the world His unbounded compassion and emotion-filled heart, especially when I may be shedding a mountain of tears of my own.

Bibliography

Ardnt and Gingrich

Galor, Katharina, and Bloedhorn, Hanswulf. The Archaeology of Jerusalem: From the Origins to the Ottomans. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013) 20.

Günther, W. “Sin.” Ed. Lothar Coenen, Erich Beyreuther, and Hans Bietenhard. New international dictionary of New Testament theology 1986: 573. Print.

Rasmussen. Carl G., Zondervan Atlas of the Bible. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2010) 242.

Schrenk, Gottlob. Ed. Gerhard Kittel, Geoffrey W. Bromiley, and Gerhard Friedrich. Theological dictionary of the New Testament 1964–: 149–150. Print.

Taylor, Joan E. “The Garden of Gethsemane: Not the Place of Jesus’ Arrest,” Biblical Archaeology Review (21:4, July/August 1995).